Implications of gendered negotiation processes on Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

- Sevinj Samadzade

- Feb 10, 2022

- 9 min read

Introduction

I started writing this article more than a year and a half ago in the midst of the escalation between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Tavush/Tovuz border during July 2020. It did not come as a surprise when just two months later a large-scale war on Nagorno-Karabakh started. Therefore, the questions raised in this article encompass consistent reality that keeps on going and yet if not addressed might keep us in this loop for a long time.

It has been almost 30 years now that predominantly androcentric negotiations process around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict continues without consensus. Since the beginning of this conflict, women’s role has been undervalued and mostly related as caregivers, and mothers, which also reflects the norm of being women in Armenia and Azerbaijan (Kvinna, 2019). In patriarchal societies where gender equality is far to come along with low political participation of women, the absence of women from the negotiations process comes as no surprise. In fact, within such patriarchal power structure inclusion of women as a homogeneous group would benefit the existing masculinized policies rather than representing the voice of different groups of women as such. Meanwhile, women’s direct participation in peace processes has the potential to transform existing power structures and achieve durable peace (Krause et al., 2018). Thus, this paper will address the implications of the gendered negotiations around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict on the overall peace processes and the importance of feminist peace interventions for transforming the conflict. It will evaluate how instead of bringing peace, the current masculinized negotiation’s process is contributing to the existing binary gender norms, hegemon masculinities and war-making. Finally, it will discuss the ways feminist conflict transformation can challenge traditional androcentric negotiations for achieving sustainable peace.

Gender norms and hegemonic masculinity perpetrating armed conflict

Gender roles and gendered power relations in patriarchal societies present femininity as the “victim” of the conflict and masculinity as the “guardian” of the femininity, which reproduces the idea of the necessity for security (Johnson, 2005, p. 53). Such gender normativity in return contributes to justification of the militarization and the escalation performed by patriarchal institutions promising more power to men and more vulnerabilities for women. Masculinity referring to the various forms in which manhood is characterized socially and culturally is not the same for all men either. Hegemonic masculinity presents the hierarchies among masculinities and how men in power not only subordinate women but also subordinate other men who have fewer privileges than them (Connell, 2005, pp. 76-79). Azerbaijan and Armenia socially and politically governed by the very same idea demonstrates militarism and war as a precondition for sustaining manhood, therefore prepares young boys since childhood for the obligatory mobilization and participation in the military (Akhundov et al., 2020, pp. 18-20);

States in crisis situations are interested in raising such masculinity for glorifying and giving a status to men for their participation in war especially to build up national collective identity (Francis, 2004, p. 5). Thus, each time escalation and large-scale military operations around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict start, states effortlessly manage to manipulate the populations and increase masculine pride through glorying men as heroes and protectors of “motherland”. Feminizing nation through this metaphor is also a part of building a collective identity around the conflict re-emphasizing the role of men as guardians of passive and weak “motherland” (Vojvodic, 2012, p. 4). Women’s assigned role as “mothers” that is obliged to reproduce for the state and army not only limits the authority to their bodies but also disempowers them from taking part in any political decision-making processes.

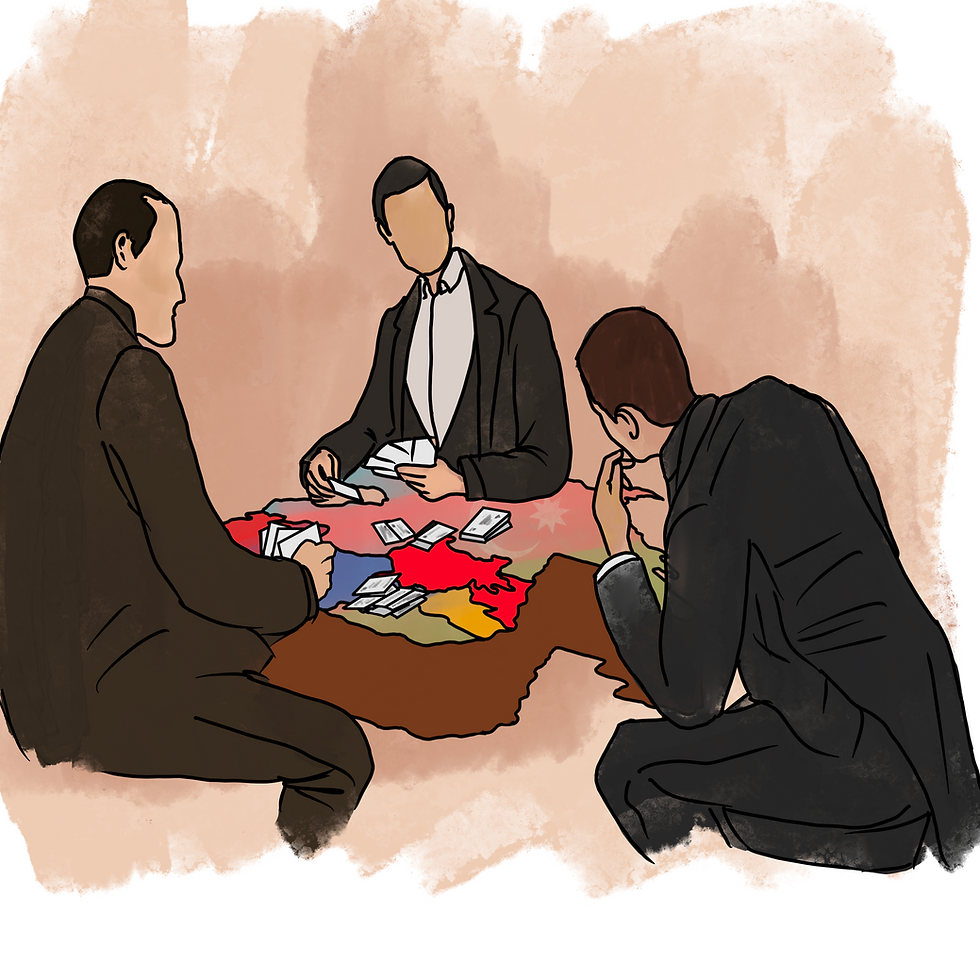

Masculinized negotiations contributing to the warfare rather than to the peace process

Being heavily militarized states, both Azerbaijan and Armenia still use the power of masculinity not only as a source for hostility and war but also as assertiveness in the negotiations processes. From this perspective peace processes taking place for many years looks like another form of competitive action that does not aim to resolve the conflict for the best interest of people, but rather represents the best interest of the business of men in power, including mediators. While Minsk Group Co-Chairs- Russia, France and the USA have been chief mediators of this conflict for a long time, their participation as impartial mediators is quite questionable as they are also benefiting from the conflict through arms’ trade with both states (Borshchevskaya, 2019, p. 12). Contrarily such hegemonic states as mediators probably contribute to controlling this all male-table and establish even more complex set of hierarchy among them.

Despite of these dependent power dynamics among mediators and conflicting states, there have been several attempts to develop the peace plan, the most recent one (before the war) being implemented since the end of 2018 until July 2020 when it failed dramatically again. Since January 2019, a joint agenda called "Preparing populations for peace" was orchestrating some hopes for positive change in peace processes as escalation on the border and line of contact had decreased and casualties were lessened (Conciliation Resources, 2019). President Aliyev and prime minister Pashinyan met in Munich Feb, 2020 holding a public debate for the first time which indicated that there was increased communication, but still same discourse and style of teaching each-other “history lessons” (Kucera, 2020). Moreover, Ministers of Foreign Affairs were continuing online meetings even during the lockdown period due to Covid-19 pandemics last being on 30 June 2020. One thing was common for all this so-called development: Untransparent and unclear agenda in full control of men in power.

Few days later on 12th of July 2020, the large-scale military operations broke on the border between Tovuz, Azerbaijan and Tavush, Armenia resulting with death of several soldiers, military officials and a civilian, followed by large-scale demonstrations by thousands of militarist men who started rallying in Baku for showing support to army and demanding more war and state military mobilization. Hostility and hatred expanded beyond borders and migrant Azerbaijani and Armenian men across the globe started violent street fights and humiliation of each-other. Overall, these dynamics shows that "Preparing populations for peace" masculinized agenda failed to contribute to peace-building among societies and instead assisted the production of more violence, aggression, enmity and even a greater war called the Second Karabakh War in September 2021.

Feminist conflict-transformation challenging traditional negotiation process

Masculinized negotiations hinder the possibility of inclusive, sustainable and positive peace which requires representation, transparency, respectfulness and a dialogue. These simple yet important elements have been missing in the negotiation table around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict but have been widely experienced by civil society actors, women’s organizations and peace-builders which have managed to develop an alternative discourse and approach to peace-building and conflict-transformation processes (Kvinna, 2019, p. 35). Nevertheless, those approaches do not manage to reach the political decision making around the conflict and especially women have always been out of those “closed doors”. It is also arguable that the inclusion of women’s voices at the negotiation table would be transformative if the overall power structures do not change. Because stereotypically women being viewed as nonassertive and willing to compromise can be easily manipulated by the same patriarchal structures which need to be challenged first. Besides, women as well as men being a socially constructed group does not hold the same experiences and the same perspectives when it comes to war and conflict. Therefore, the inherency of understanding women’s struggles for peace and contributions to conflict transformation comes along with also understanding women’s participation in and support of wars and militarization (Sharoni, 2010, p. 6). Either by serving in the military or by producing ideas and emotions for militarization, for instance through singing patriotic songs or teaching nationalistic history, women in Armenia and Azerbaijan often do not only perform the stereotypical role of mourning mothers.

Feminist intervention to the conflict is rather transformative than simply negotiating or resolving the conflicts. It also raises a lot of critical questions when it comes to analyzing conflict and violence as well as understanding peace, and relating to it (Sharoni, 2010, p. 13). The absence of women in the current political decision-making around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is an outcome of women’s overall oppression and subordination in Armenia and Azerbaijan. Within the current reality of gender injustices and violence on the ground, and the constant disempowerment, exploitation and expropriation of women directly affected by the conflict or currently living in the conflict zone explains why within such circumstances peace is only an abstraction. It also generally explains how despite of advocating for the importance of women’s participation in peace processes, as highlighted in UN Security Resolution 1325, not much has changed since its adaptation (Krause et al., 2018, p. 987). While patriarchy disvalues women’s work, and abilities, it also constantly reproduces itself by the construction of masculinities that guide militarism. In response to that, the feminist transformation of oppressive gender relations would make war and militarism, and systems that produce them no longer viable.

The necessity of solidarity through just representation rather than subordination

Rejecting the traditional masculinized diplomacy, the feminist vision for peace-building includes expanded solidarity between women’s civil society groups and their representation at the peace processes or in the establishment of alternative peace processes. Krause (Krause et al., 2018, p. 990) argues that sustainable and positive peace is more likely through the connection between female signatories and women civil society groups that are well aware of their local contexts and aim to address socio-political inequalities. This connection will unlock the current chain of secret, elitist and unreachable negotiations by directly communicating the needs of communities and responding back to them with openness about the negotiations process so that they are prepared and effectively mobilized. In the case of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, there are a few experienced women peace-builders who are working at the grass-roots level and their representation in the negotiations table has the potential to build those connections not only between peace signatures but also between communities in conflict so that post-conflict transitional justice, reconciliation and rehabilitation process goes hand in hand. In addition to that, alternative peace processes including developing culture of peace within and between societies will transform all forms of violence and injustices established by political, cultural and social institutions.

However, the current political realm in Armenia and Azerbaijan where local women’s peace initiatives are challenged by the states is pushing women’s struggle for peace and justice to the level of the necessity for increased political struggle. While trying to suffocate the voices of feminist peace-builders, from time to time both states also cover this up by showcasing the peaceful messages of the female partners of the heads of the both patriarchial states. These imitations are quite contradictory to their own long-lasting state propaganda and militaristic policies that have resulted in a lack of trust and much hatred between societies. Being fully allied with the structures that reproduce gender inequalities as well as militarism, this “peace” portrayal of female power-holders disregard the power of women’s voices and demands by again shielding the militarized masculine agendas with ruling-class feminine faces.

Conclusion

Thus, gendered negotiations and the absence of women in the decision-making process around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict have negative implications not only for finding the common ground and resolution, but also it has limitations for maintaining a sustainable and transformative peace process. This means that, unless the gender and power dynamics shift in the political and social level, the negotiations will have only a double-edged sword effect for both societies, reproducing more violence and systems that justify it. As long as the idea of manhood in its gender-binary definition will be linked to participating in war and heroism around it, less can be expected off any peace process. It is clear now that “Preparing populations for Peace”- another “gentlemen’s agreement” continuing for a year and a half, stopped imitating the peace agenda and gave a grand space for further military interventions.

Meanwhile, the feminist approach to peace-building and conflict transformation has a power to challenge the male-dominant gender order that is governing both war and peace processes by establishing solidarity among women’s civil society groups and expanding their representation at all political decision-making, including negotiations around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Here it will be possible to develop an alternative peace process to the traditional diplomacy driven by hegemonic masculinity, through rejecting elitist peace-making, transforming gender norms and relations, as well as considering various experiences, needs, and voices of women in relations with conflict. Yet it is hard to presume the possibility of such development anytime soon when the current conjunction of capitalist patriarchal structures and militarism remains powerful.

References

Akhundov et al. (2020). Conflicts and Militarization of Education: Totalitarian Institutions in Secondary Schools and in the System of Extracurricular Education in Azerbaijan (Part 1). Caucasus Edition, 18-20.

Borshchevskaya, A. (2019). Foreign Perspective on the Russian Role in Conflict Between Armenia and Azerbaijan. Washington: Washington Institute.

Conciliation Resources, C. (2019). Preparing populations for Peace: Implications for Armenian-Azerbaijani peacebuilding. London: Conciliation Resources.

Connell. (2005). Masculinities. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Francis, D. (2004). Culture, Power Asymmetries and Gender in Conflict Transformation. Berlin: Berghof Foundation Center for Constructive Conflict Management.

Group, C.-C. o. (2019, January 16). Retrieved from https://www.osce.org/minsk-group/409220

Hakobyan, A. (2020, July 13). https://wfp.annahakobyan.am/en. Retrieved from https://wfp.annahakobyan.am/en/2020/07/13/a-call-to-stop-the-military-operations-and-move-towards-peace/

Johnson. (2005). Gender Knot. Pearson Education India.

Krause et al. (2018). Women’s Participation in Peace Negotiations and the Durability of Peace. International Interactions, 44:6, 985-1016. doi:10.1080/03050629.2018.1492386

Kvinna, K. t. (2019). Listen to Her: Gendered Effects of the Conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh and Women's Priorities for Peace. Tbilisi: UP, LTD.

Sharoni, S. (2010). Conflict Resolution: Feminist Perspectives . International Studies Association and Oxford University Press.

The Female Advantage . (2003). In L. B. Laschever, Women Don't Ask: Negotiations and the gender devide (p. 164). New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Vojvodic, N. (2012). Gender Analyzes in Ethnic Conflict: Causes and Consequences in case of Yugoslavia. University College London.

Walsh, S. (2014, October 04). Nagorno-Karabakh: a gender inclusive approach to peace. Retrieved from Open Democracy: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/nagornokarabakh-gender-inclusive-approach-to-peace/

Comments