“Some angels have a moustache”

- Toğrul Abbasov

- Dec 17, 2021

- 20 min read

Introduction

Exhilarated by the advantages of the Azerbaijani army during the heated days of the 2020 Karabakh war, an Azerbaijani female social media user shared a picture of Ilham Aliyev raising his fist in the air and commented: “Some angels have no wings, they have a moustache”. Apparently, this comment was so much liked that similar posts were repeated by other Azerbaijani users. Imagining a moustached (and aggressive) man as an angel was the harbour of image travesty not encountered before the war.

Despite the inherently distinct portrayal of angels in various belief systems[1], in Azerbaijan, they are portrayed using women or girls. According to the Dictionary of Azerbaijani Language, an angel “is a winged heavenly being with an image of a beautiful woman that fulfils the orders and commands of Allah”. A moustache, on the contrary, is a symbol of masculinity. Again, referring to the Dictionary of Azerbaijani language, moustache “is a bush of hair on the upper lips of men that are not shaved and preserved”. Traditionally, a moustache has great importance in Azerbaijani society. For instance, in “Atları Yəhərləyin” (“Saddle the Horses”) (1985) as a punishment, Gachag Nabi shaves the half of moustache of the village foreman, who does not know how to bear this humiliation but to commit suicide. One of the praises to Gachag Nabi in the epos is about his “curled” moustache. Moreover, those lines are also among the verses of this epos selected for “Min Beş Yüz İlin Oğuz Şeiri” (“Oghuz Poetry of Fifteen Hundred Years'' – translator note) anthology (1999:523)[2]. In “Arşın Mal Alan” (1945), Soltan bey talks about his moustache to emphasize his masculinity and noble status: “I don’t eat plov with beys so as not to get my moustache greasy”. We can bring more examples of moustaches as a symbol of masculinity.

Given the above mentioned, how can we interpret the embodiment of symbols of femininity (an angel) and masculinity (a moustache) in the image of a country leader and military army commander? Guided by this example, can we understand whether any differences exist between women and men in their approach to war? Or, in some sense, is the war itself a challenge to traditional gender roles that nationalists strived to shape? Can the line between femininity and masculinity be erased in a manner completely opposite to what is expected by feminist and queer theories? In this article, I will try to shed light on these questions. By exploring relations between nationalism, militarism, and gender, I will first present a short summary and perspectives of various theories on this topic. Thereafter, I will scrutinize the nation-building and gender roles from a historical perspective for the case of Azerbaijan. In the last part, I will analyze nationalism, militarism, and gender roles in mass media around, before and after the Karabakh war, as well as the example that I presented above and attempt to address my questions.

Gender images of the nation

After establishing the national state by consolidating feudal states in Italy, 19th-century Italian politician and theoretician Massimo d’Azeglio said in the first assembly of parliament: “We have made Italy, now we have to make Italians” (Hobsbawm, 2000: 44). This statement explained the foundations or roots of several analyses on nationalism presented later. Although some theoreticians have claimed that nations and nationalism have preceded history and been part of human existence somehow naturally (primordialists) or since ancient times (perennialists) (Smith,1986;12)[3], modernist theorists like Eric Hobsbawm (1983:1991), Benedict Anderson (1983), and Ernest Gellner (1983)[4] have introduced an idea that a nation is a modern construct, invention or imagination created by nationalist elite and governments as a result of several technological, economic and cultural events. If we can talk more openly, according to modernist theoreticians, “nation is created by nationalists and is a product of modernity”. There exist various theoretical approaches to how, when and where this nationalist construct or “invention” (Gellner) has been established.

Anderson is more inclined to link it to cultural changes in the modern era. According to him, unlike rationally adopted ideologies, nationalism was born within cultures that preceded it and shaped by integrating/opposing these cultures. That is, a nation (as claimed by Geller) is not an artificial invention and has strong cultural origins (Anderson, 2006: 9-37). It has become possible to use and spread these origins to wide masses with the development of the capitalist print industry. Gellner claims that social changes and mobility generated by the Industrial Revolution has been more important. These changes have not only created centralized states (national states) but also induced those to consolidate masses around the same goal and high and homogenous culture (language, education) by enlightening them for political and economic reasons. Sharing similar views with Gellner, Hobsbawm emphasized the role of political needs. According to him, a nation is an invention serving ideological hegemonies, and “national consciousness” is the most obvious and widespread example of invented traditions (2000: 80-101).

However, it is interesting that none of these theoreticians has put forward the relations between gender roles and nation-building. For instance, Hobsbawm stated that duties that serve the political unity representing the nation were prioritized over social duties and all duties in certain exceptional cases. According to him, that was the difference of modern nationalism from ethnic units of previous periods – being assigned duty for the nation (2000: 80-101). Despite that, Hobsbawm was not concerned with the following question: “Are “duties assigned” to men and women similar in the process of nation-building?” Feminist scholars were the ones to have introduced a critical review of nationalism by asking this question. In particular, early interventions by researchers like Cynthia Enloe, Nira Yuval-Davis, Floya Anthias, Kumari Jayawardena, Sylvia Walby, and G.L. Mosse has been critical. [5]

For example, in Woman-Nation-State (1989), co-editors Nira Yuval-Davis and Floya Anthias show that control over the sexual lives of women is an integral part of nation-building. They distinguish 5 duties (national roles) of women within a nation in the introduction:

a) as biological reproducers of members of ethnic collectivities;

b) as reproducers of the boundaries of ethnic/national groups;

c) as participating centrally in the ideological reproduction of the collectivity and as transmitters of its culture;

d) as signifiers of ethnic/national differences - as a focus and symbol in ideological discourses used in the construction, reproduction, and transformation of ethnic/national categories;

e) as participants in national, economic, political, and military struggles.

That is, Yuval-Davis and Anthias determine that women’s role in the national project are often realized through the preservation and transmission of “national culture” via giving birth and educating children (a-b-c), sometimes as symbols (a), and more rarely through joining national struggle directly (e) (1989: 8-11).

The important point here is also the extent to which these “nationalist duties” are voluntary, mandatory, or emancipatory in terms of women rights. How did women benefit from separating from feudal patriarchy and joining the “nationalist project as citizens”?

In Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World (1986), Jayawardena has mainly investigated this topic concluding that anti-imperial nationalism in the third world has a benevolent impact on women’s freedom. In this manner, the author presents cases from several third-world countries (India, Egypt, Afghanistan, Indonesia, etc.) and demonstrates the close relationship between early feminist movements and nationalist movements at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries. According to her, all these countries were captives of imperialism; for that reason, feminist and anti-imperialist nationalist movements were intertwined. To demand their rights, women often acted as a sidearm of organized nationalist movements mostly consisting of men and rarely as independent entities.

Hence, Jayawarden stated that it is impossible to understand feminism on one hand and nationalism on the other hand without taking into account imperialism and capitalism. The idea that we can describe the “demand of equal citizenship rights” as opposed to imperialism represented the common interests of feminists and anti-imperialist nationalists. Unlike first world countries, granting universal suffrage to women alongside men at the same time in several third world countries can be an illustration of this idea.

The myth of equal citizenship (staatnation) was one of three myths in national projects described by Yuval-Davis’s modernist theory in her later work Gender and Nation (1989). According to Yuval-Davis, other national myths were the legendary myth of common origin (volknation) and the myth of common culture (kulturnation). In this work, Yuval-Davis criticizes the “myth of equal citizenship” alongside other myths and its exclusionist nature (2008:5-21), for according to Yuval-Davis, the precise description of citizenship (like other notions) is not possible. Like various definitions of citizenship in different states and societies, different groups are attributed different statuses within the same society, and those change throughout time. This is also the case for the citizenship status of women. The citizenship of women can be understood not only in comparison to men’s citizenship but also by taking into account whether they belong to a hegemon or oppressed group, their ethnic and cultural origins and whether they reside in urban or rural areas (2008:69).

Cynthia Enloe (2000) defends the idea that nationalist movements have not brought freedom to women within the concept of citizenship. Enloe demonstrates with examples that nationalism is created with masculine history and memory, and the fear of masculine shame and humiliation, as well as masculine hopes, are used while drawing them to the fore. According to Enloe, national liberation movements have not played a significant role except replacing the male hegemony representing imperialism with the male hegemony of local men in newly established national states.

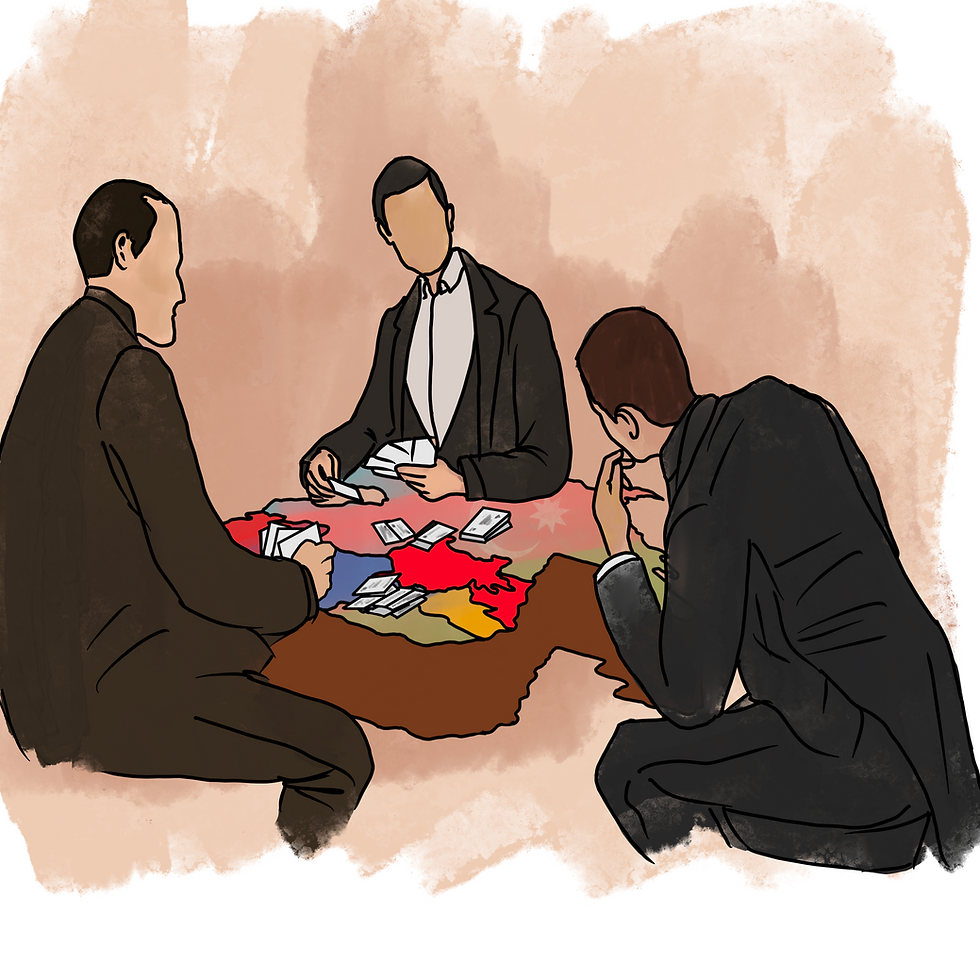

“Given the scores of nationalist movements that have managed to topple empires, create new states, and unsettle existing states, it is surprising that the international political system has not been more radically altered than it has. But a nationalist movement informed by masculinist memory, imbued with masculinist pride, and holding a patriarchal vision of the new nation-state is likely to produce just one more actor in an untransformed international arena. A dozen new patriarchal nation-states may make the international bargaining table a bit more crowded, but this will not change the international game being played at that table” (Enloe 1990: 64).

Enloe has also brought into light militarism and gender relations. She drew attention to gender roles of militarist global strategies and their relation to various “masculinity constructs”. According to Enloe, women’s integration to the state or to other militarist groups does not alter gender-based identities and expectations of those institutions and groups. In other words, women do not render either army or peace talks “gender-neutral” immediately by simply participating in those. They join structures inherently determined by the norms, environments and forms of expression that are shaped by masculine values.[6] In short, these structures like all modern institutions are “gendered institutions” (2000).

Images of Women of Azerbaijani Nationalism

In the foreword to the Women Encyclopedia of Azerbaijan published in 2002, Ramiz Mehdiyev, former head of the presidential administration and leading ideologue of 30 years of post-Soviet Azerbaijan, emphasized the prominent role played by women in the rich and ancient history of Azerbaijan and added: “As we always consider women as gentle beings, we would never want them to endure hardships our males had gone through. But what we can do, our women have lived through troubles and tragedies faced by our nation and endured losses and hardships from time to time”. The fact that women have had to go beyond the role assigned to them is a sigh of frustration not only for Ramiz Mehdiyev, but also for Azerbaijani men dutied to be protectors of women. But it was always foreigners and enemies who have caused these feelings of frustration: “It has been so during the political fluctuations at the beginning of the XX century, repressions, years of the hardship of the world war as well as in periods of escalated Armenian aggression towards Azerbaijan at the end of the century” (Mehdiyev, 2002: 5-8).

In Nationalism and Sexuality: Respectability and Abnormal Sexuality in Modern Europe (1985), George Mosse, one of the first to scrutinize relations between nationalism and gender, has stated that the structure of a nation is determined by men and masculinity, and women have prepared the backdrop. According to Mosse, the myth of “male protector” led to the emergence of the myth of “protected woman”. But “chastity and honour of women” is the main thing to be protected. The protection of chastity and honour is the duty of a woman and freedom of a man from “national humiliation”. The frustration expressed for some cases in the foreword of the Encyclopedia is burdened with the frustration for the inability of women to fulfil their duties, that is, to protect their chastity by staying in the backdrop as desired. But this feeling does not pertain to this text only.

In her article Guardians of the Nation: Women, Islam and the Soviet Legacy of Modernization In Azerbaijan, Nayereh Tohidi (1998) shows that an Azerbaijani woman is always assigned a role of a protector of honour. According to Tohidi, an Azerbaijani woman has been the object as well as the subject of nation-building during the Tsarism, Soviet and post-Soviet periods. The image of a "virtuous woman" has constituted the foundation of the “us and them” structure especially in relations with Russia and occupied a special place in the building of national identity (1998:163-165). Thus, although women have somehow played an active role in social life in the Soviet period, they were not liberated from the “duty to protect their honour” in daily and family life in accordance with patriarchal norms and customs. Moreover, it could not be said that there was full equality between men and women in social life during the Soviet period (1998:142-145).

Like in other third world countries, the “woman problem” in Azerbaijan has been one of the main parameters of modernization and national construction ever since the Tsarist period. Newly formed national bourgeoisie and educators have thought that women’s role must be modernized as well. However, this claim was aimed at “an educated and modern mother” role rather than the liberty and equality of women. An article titled “We must educate ourselves” by Shahrabanu Shabanzade in the first woman journal “Işıq” (“Light”) published in 1911 is the summary of the main enlightenment ideas of the era:

“Yes, as mothers of humanity and spirit of mankind, women must be educated before everyone else. But we have departed from this rule and caused the decline of our nation. Thus, we need to educate ourselves to overcome and isolate this trouble and to flourish our press that is the locomotive of progress! Let’s educate! Let’s try to educate ourselves! We need to educate, educate ourselves!!!”[7]

On the other hand, the fact that Taghiyev’s school for girls was expensive and taught household chores alongside the school curriculum shows that Azerbaijani bourgeoisie and enlightenment “did not consider true liberty of women and progress of their status”. That is, regardless of its modern or conservative nature, the nationalist-enlightenment perspective on the “woman problem” has emerged from the combination of “selected specific reforms” and “own values” (western science + our morality) (Tohidi, 1998).

Even after 100 years that have passed, the similar framework of notions of “national woman” or “national feminism” is not a coincidence, but an indicator of the continuity of the national project. For instance, Aysel Alizadeh, the editor-in-chief of qadinkimi.az claimed to be the first feminist website, gifted the launch of the website to the “national republic” announced in 1918.[8] Moreover, in her article “Turk woman wore coloured kalaghayi, did not cover in black”, she claims that the problem of women in Azerbaijan emanates from the fact that women are not national enough: “Dear women, let's own the kalaghayi, our national identity. Let’s give new life to our scarf. Let’s remember that we are masters. What do you say?” [9]

This “woman construct” formed within the triangle of religion, tradition and nation can also be observed in Jill Vickers (2006). According to this author, many Azerbaijani women prefer to stay at home more than to participate in social life. Vickers has prepared a comparative scheme of 30 different countries and showed that women may not strive for participation in social life that is related to the state structure. In contrast, they may not support feminism and want to “return home”. Men have acquired social roles in those locations and activated nationalist movements. In this sense, Azerbaijani women mainly belong to the category supporting the nationalist project and preferring “to return home” (2006:88). That is, the support for the idea of protecting women at home/in the background by women can be seen as a success of the national project of Azerbaijan.

But it must be taken into account that it is not only the physical body of a woman but also “the body of motherland” is under protection in this nationalist worldview. The representation of homeland as a woman’s body in the nationalist discourse is used to construct a national identity based on the unity of males in a nation composed of male brothers. “If a nation is a symbol of male unity, homeland is a woman whose body must be protected” (Afsaneh Najmabadi, 1997). In her article The Erotic Vatan [Homeland] as Beloved and Mother: To Love, To Possess, and To Protect where sexual relations between Iranian nationalism and homeland is investigated, Najmabadi describes the bond of honour between nation and homeland in the following manner:

Rooted in Islamic thought, namus was delinked from its religious affiliation [namus-i Islam] and reclaimed as a national concern [namus-i Iran], as millat itself changed from a religious to a national community. Slipping between the idea of purity of woman ['ismat] and integrity of Iran, namus constituted purity of woman and Iran as subjects both of male possession and protection: Sexual and national honour intimately constructed each other. [10] (1997:444)

The associative power of the notion of honour between homeland and woman is also valid for Azerbaijan. Thus, the situation on the isolative potential of equal citizenship rights emphasized by Yuval-Davis is clearly observed in the case of Azerbaijan. Citizenship roles change depending on the direction of nationalist discourse. The most obvious situation in this regard is the moments of crisis, that is, war situations. Enloe claimed that male dominance is strengthened when the nationalist movement is militarized. On this basis, Enloe shows that every element that is related to the army obtains extremely masculine features of (1990:56). So to speak, the myth of equal citizenship promised by nationalism is completely abolished during militarist times; it turns into a citizen that a war (militarism) requires - into “an angel with a moustache”.

“Our Woman – Enemy Woman”

In Orientalism (1979), Edward Said shows that, parallel to the Western colonialist policy in the East, two images of femininity contradicting and complementing each other are formed in orientalist works. The first image is the “feminine orient”. “Feminine orient” as erotic attraction and anti-rational passion is a place that calls Western imperialists to “invade”, “enter (dark/mysterious corners)” and fulfil their erotic dreams by capturing her. “This is especially clearly seen in writings of travellers and novelists: women are usually the product of male imagination. They are the expression of boundless lust, completely silly and eager”. Another image is the “caressing female west” that must be protected from the violation of a “barbaric eastern man”. As a result, although distinct from each other, both a place to be occupied and a place to be protected are portrayed as female bodies.

The narrative created around the Karabakh conflict between Azerbaijan and Armenia is often brought to attention through the “dualist female body” described by Said. On one hand, there is the sado-erotic “breasts of our women have been cut” rhetoric and “violation of Azerbaijani pure women by barbaric Armenian men” narrative, on the other hand, there is “an Armenian woman as an erotic object eager to be raped”.

There exist numerous examples. Even before the war, there were many materials claiming “the doings of Armenians to Azerbaijani women” both in mass media and books. For example, Zaur Aliyev, the employee of ANAS and Doctor of Philosophy in politics, made the following claims in his article titled “Methods of Armenian torture” rich with depictions of torture, murder, and rape methods:

“Armenians would cut up the bellies of captive pregnant women especially from Khojaly and feed the fetus to dogs, fill woman’s belly with shells, living cats, snakes, frogs, rats, etc., sew the wound and watch her die in pain.”

Or

“Armenians would rape all girls and women from age 4 to 60 one by one and would force them to dance naked. A captive mother that could not bear her 6-year-old daughter’s rape has smothered herself with a rope, another has killed herself with a pitchfork when she was taken to work. Among captive Azerbaijani girls, those whose virginity was preserved were given to Armenians visiting Karabakh from abroad or high-ranking bureaucrats of foreign countries as presents".

The author claims that this information is based on “witness’ statements, data of the Ministry of National Security, reports of “The State Commission on Prisoners of War, Hostages and Missing Citizens”, war participants and writings of Armenian authors”. Given that he does not provide any sources on which this information is based, it seems more like it is the product of “national imagination”.[11]

Joane Nagel wrote that “Enemy women are always portrayed as sexually frivolous, easily seized and as one type: whores, prostitutes or legitimate rape objects”. In this sense, Armenian women were often brought to attention by mass media as images of “legitimate objects of sexual assault”. For example, in an article “Fahişəlik ilahəsinin erməni gözəlçələri” (“Armenian effeminates of the goddess of prostitution”) published in 2011 in modern.az website, it is claimed based on “sources” that Armenian women have been historically and are currently engaged in prostitution and concluded:[12]

“It is therefore clear that Armenian prostitutes know no boundaries to spread their viruses. Indeed, that is the true face of Hay males and females! If women of a nation are prostitutes and men are effeminates, any perversion can be expected from them. Thus, we understand that we are facing not men, but nongenders who have acquired prostitution as an occupation!”.

Another example does not only emphasize the prostitution of Armenian women, but also “their invitingness that seduce our men”. An article titled “Ermənistanın qədim peşə sahibləri türk kişilərini necə yoldan çıxarır?” (“How do adherents of the oldest occupation seduce male Turks?”) is concluded by finding “the culprit of all troubles Azerbaijan endured”:

"To be honest, historical facts that were unearthed while investigating the roots of prostitution in Armenia have helped us to find an answer to a problem concerning us for a long time. It is now evident which feature of Armenian girls always seduced our careerists, personas occupying high ranks in the country, and young and promising writers during the Soviet period (those interested can observe the admiration of Armenian women by our new writers and publicists in social media - ed.) and Turkish men in Turkey"...

The most important part of the article is that it associates Armenia with “a prostitute woman” as a territory. Under the subtopic “Ermənistanda əxlaqsızlıq üçün münbit şərait” (“Fertile conditions for immorality in Armenia”), the Turkish media referring to Armenian sources asserts that the prostitution in Armenia flourishes not only due to economic hardships. In the blog of Turkish Armenians, it is mentioned that there are natural conditions for prostitution. It is said that “According to the official statistics of 2001, 2.1 million out of 3.15 million population, that is, more than half of population are women. Given that more than half a million working-age males have departed to Russia and other countries for work, it is not hard to imagine the demographic balance of the country” strengthening the emphasis on “Armenia lacking masculinity”.[13]

In addition to the above mentioned, the image of “a prostitute enemy woman” is turned into an image of the enemy and enemy geography to extend the representativeness of this image during the war period. In other words, an enemy body becomes “a female prostitute body” to be captured. It is the logic that is followed during, as well as in the aftermath of the recent war. The news related to fighting women on the Armenian side during the war are given the following titles: “Ermənistanda kişi qalmadı: Qadın könüllülər cəbhəyə göndərilir”[14] (“There are no men left in Armenia: Female volunteers are sent to the frontline”), “Erməni qızların hər kəsi güldürən hərbi təlim görüntüləri”[15] (“Military training videos of Armenian girls ridiculed by everyone”), and “masculine power of male Azerbaijan” and “weakness of female Armenia” are exaggerated. The war in some sense is an “invitation to masculinity” (Mosse,1985: 34). But we must be aware of “female Armenia’s” crafts (“specific to women”), because “Armenians send their women to the front with different purposes”. In an article with a similar title, a former Azerbaijani female fighter warns Azerbaijani men to be careful about this craft:

"There is no need for Azerbaijani women to go to war. Our men, our brothers, fathers, and husbands are brave warriors. Wherever there is a need to serve our soldiers, our women will be there. We have a lot of women in military service. We don’t want to fight with their women. We want to fight with their men. It is a disgrace for an Azerbaijani woman to fight with Armenian women. Those women are like insects to us. When they send their women to the front, they instruct them not to fight, but to seduce Azerbaijani men".[16]

The discourse of “female Armenia” and “Armenia that lost its masculinity” continued after the war as well. In several articles and news titled “Ərsiz qalan Erməni Gəlinləri: Xankəndidə süni mayalandırma ilə doğub-törətmək planı.”[17] (“Widowed Armenian women: the plan of reproduction in Khankendi by artificial insemination”), “Maviləşən Ermənistan ordusu”[18] (“Queerified army of Armenia”), “Erməni Qadın Sülhməramlıları Satdı”[19] (“Armenian woman sold out peacekeepers”), “Ermənilər “ağır artilleriya”nı işə salıb: Xankəndində erməni qız rus sülhməramlısından hamilə qaldı”[20] (“Armenians have fired “heavy artillery”: an Armenian girl was impregnated by a Russian peacekeeper in Khankendi”), Armenia is portrayed as a “feminized” land that “has lost its masculinity” and hence, acquired the features of a “prostitute woman” as in patriarchal imagination. There are so many images of Armenians as “prostitute women” and “women deserving to be raped” in social media that those are beyond the scope of this paper, and their number is growing. As emphasized by Cynthia Enloe, “women are either icons protected and sanctified by the nation or war trophies to be captured and humiliated. In both cases, real players are the men protecting their freedom, honour, dignity, their homeland and women.” (1990: 45)

Conclusion

Although nationalism starts with “citizens with equal rights”, citizens have started to implement gender roles in accordance with the national project and hegemony of “imagined traditions” after national states were established and the nationalist ideology gained the dominant position. In Azerbaijan, these roles are determined by “male honour” (moustache) and “female chastity” (angel). However, when the nationalist project is militarized, these roles are put into a new framework in men’s favour. The militarism filled with masculinity combines “moustache and angel” in men’s favour as well. The image of “an angel with a moustache” during the 2020 Karabakh war can be seen as a unifying power of militarism. But we must remember another symbolic event taking place after the war. A patriotic female journalist who interviewed a war veteran has publicly disclosed that she was sexually harassed by him. That is, the war was over, the moustache and the angel were delinked, and it was time to restore the gender roles of males and females as citizens.

References

Anderson, Benedict (2006). Imagined Communities(reprint). Verso.London.

Enloe, Cynthia (1990). Bananas, Beaches, Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics.University of California Press.

Enloe, Cynthia (2000). Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women's Lives. University of California Press.

Gellner, Ernest (1983). Nations and Nationalism. Basil Blackwell Publishing. Oxford

Hobsbawm, Eric. and Ranger, Terence (1983). The Invention of Tradition.

Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Hobsbawm, Eric (2000). Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. (Second Edition). Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

Jayawardena, Kumari (1986). Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. Zed Books. London-New Delhi.

Mehdiyev, Ramiz (2002). Azərbaycan Qadın Ensiklopediyası.Azərbaycan Milli Ensiklopediyası Nəşriyyat-Poliqrafiya Birliyi.Bakı.

Mosse, L. George (1985). Nationalism and Sexuality: Respectability and Abnormal Sexuality in Modern Europe. Howard Fertig. New York.

Najmabadi, Afsaneh (1997). The Erotic Vatan [Homeland] as Beloved and Mother: To Love, To Possess, and To Protect. Comparative Studies in Society and History, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Jul. 1997), pp. 442-467.

Said, Edward (1978) Orientalism. Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

Smith, Anthony (1986). The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Blackwell Publishing.

Tohidi, Nayereh (1998). “Guardians of the Nation- Women, Islam and the Soviet Legacy of Modernization In Azerbaijan” Women in Muslim societies: diversity within unity. Ed: N. Tohidi & H.L. Bodman. Lynne Rienner Publishers. Colorado.

Vickers, Jill (2006). Bringing Nations In: Some Methodological and Conceptual Issues in Connecting Feminisms and Nationalisms. International Feminist Journal of Politics, 8:1 March 2006, 84–109.

Yuval-Davis, Nira &Anthias, Floya (1989). Woman- Nation-State. MacMillan Press. London.

Yuval-Davis, Nira (2008). Gender and Nation(reprint). Sage Publishment. London.

Notes: [1] The image of an angel can be represented differently in various mythologies, religions, and their different branches. In Islam, angels are “supernatural beings that can take different forms and are not perceived with senses”. According to the Quran, unlike humans and demons, angels are believed to be created from light, do not eat or drink, can be of great size and strength depending on their tasks and can have multiple hands and wings that represent their power. The Quran also rejects the feminine description of angels and naming them as “god’s daughters” by idolaters and emphasizes that angels have no gender. (TDV İslam Ensiklopediyası:https://islamansiklopedisi.org.tr/melek) [2] “Min Beş Yüz İlin Oğuz Şeiri” (“Oghuz Poetry of Fifteen hundred years”) antology project is developed by Nazim Ibrahimov, and compiled and commented by writer Anar Rzayev. [3] It has been shown in various ways that primordialist and perennialist approaches have lost their credibility in academic circles except in propaganda by nationalist ideologues and leaders. Some researchers have stated that these approaches have no ground to be perceived seriously, and others have emphasized that those must be excluded from sociological literature altogether. However, some scholars such as Anthony Smith have emphasized the importance of perennialist research in particular and its significance in understanding ethnic symbols, discourses and memories (Smith,1986:192). [4]The Invention of Tradition (1983) E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger; Nations and Nationalism since 1780 Programme, Myth, Reality (1991) E. Hobsbawm; Imagined Communities (1983) Benedict Anderson; Nations and Nationalism (1983) Ernest Gellner. [5]G.L. Mosse- Nationalism and Sexuality: Respectability and Abnormal Sexuality in Modern Europe, (1985); Kumari Jayawardena - Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World (1986); Cynthia Enloe - Bananas, Beaches, Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics (1990); Cynthia Enloe - Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women's Lives (2000); Nira Yuval-Davis ve Floya Anthias (ed.)-Woman- Nation-State (1989). Nira Yuval-Davis- Gender and Nation (1997) [6] For instance, according to the recent research published in Guardian in July, 2021, two-third of women serving in the English army have been subject to sexual harrassment and assault: https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2021/jul/25/two-thirds-of-women-in-uk-military-report-bullying-and-sexual-abuse [7]recounted by: http://www.anl.az/down/meqale/xalqcebhesi/2014/aprel/361398.htm [8]https://musavat.com/news/aysel-elizade-azerbaycanin-ilk-feminist-saytini-acdi_526410.html?fbclid=IwAR2zD-G7neWpZz_jGdMpmHd_NvKmUNA22y3-wxoTGeEIrxXyacGPeMV0Xyc [9]http://qadinkimi.az/az/turk-qadini-rengli-kelaayi-balayib-qara-rtukde-gezmeyib/?fbclid=IwAR0GJ2u5PGulwwf3bGbp07H99vQ3MDyWR9dreIM5BlQ7bPSpDpV9ptyA1yc [10]Afsanah Najmabadi investigates the formation of nationalism (and nation) and gender relations in Iran more in detail in her book Women with mustaches and men without beards: gender and sexual anxieties of Iranian modernity published in 2005. Najmabadi emphasizes the heteronormativity of male love towards “female homeland” alongside the modernisation and, at the same time, states that it is a departure from homosexual love pertinent to Sufi tradition of Iran (2005:2). In short, “erotic homeland” was not only dream, but also a heteronormative desire constituting the foundation of nationalism. For more details, see: Women with mustaches and men without beards: gender and sexual anxieties of Iranian modernity (A.Najmabadi,2005,University of California Press) [11]http://www.nuh.az/23325-ermni-ignc-nvlri-ok-fotolar-18.html [12]https://modern.az/az/news/18085 [13]https://news.milli.az/armenia/37004.html [14]https://oxu.az/war/432490 [15]https://baku.ws/karabakh/101270 [16]https://modern.az/az/news/261595/ermeniler-qizlarini-cebheye-basqa-meqsedle-gonderirler-kecmis-doyuscu-qadindan-cagiris [17]https://yenisabah.az/ersiz-qalan-ermeni-gelinleri-xankendide-suni-mayalandirma-ile-dogub-toretmek [18]https://kaspi.az/az/mavilesen-ermenistan-ordusu?fbclid=IwAR2b5Z7UXPmJqP0hme9vb3O3Ab3nFsUwqw91LsetpoE56w-R6db3aIcxTJU [19]https://oxu.az/society/521416 [20]http://pia.az/ermeniler-agir-artilleriyani-ise-salib%E2%80%A6-%E2%80%93-xankendinde-ermeni-qiz-rus-sulhmeramlisindan-hamile-qaldi-398825-xeber.html

Comments