LGBTQI+/Queer Experiences in the Context of Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict

- Ramil Zamanov

- Nov 20, 2021

- 11 min read

Introduction

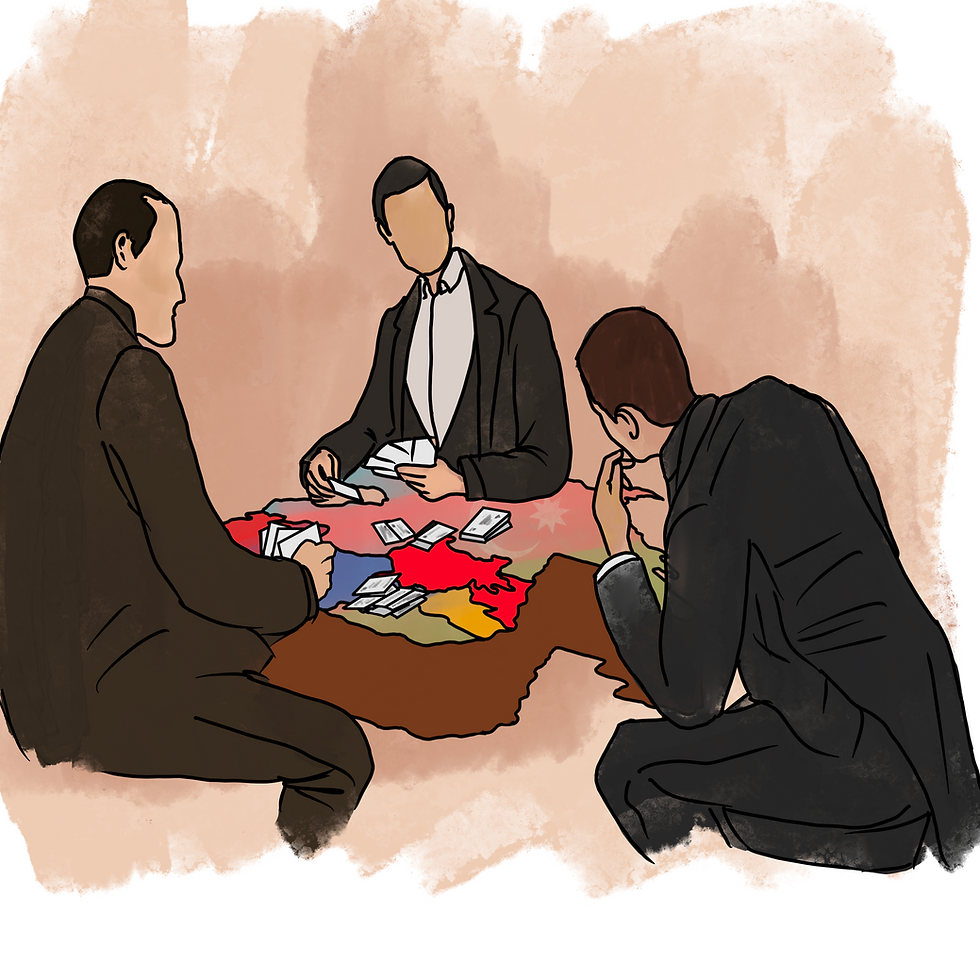

The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is a territorial and ethnic conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh that has led to war, displacement, trauma and continuing animosities. One of the important reasons for considering peacebuilding is its continuing significance in the current frozen peace negotiations among the governments of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Nagorno Karabakh. For more than thirty years, people have been living in uncertainty and often precarity while in recent years the governments of Armenia and Azerbaijan have increased their military spending (Mutschler, 2017). This can be considered an indirect sign for gradually stopping the peace negotiations and resolving the conflict with military means. For many years, the lack of effective and accessible peacebuilding between Azerbaijan and Armenia has led to a serious weakening of peace activism in both countries. At the same time, the existing phobic propaganda on both sides has strengthened anti-pacifist positions in the process. Proponents of peace in both Azerbaijan and Armenia are constantly under pressure, and even those with anti-war views in Azerbaijan have been summoned to police stations (Abubakirova, 2020). The Armenian-phobic and Azerbaijani-phobic way of thinking has been constantly spread by this phobic propaganda through television, press, radio and other means (Akhundov, 2017). For this reason, peace activism has been subjected to a deplorable situation in both countries.

Existing initiatives aiming at peacebuilding in the conflict on Nagorno Karabakh have been criticized for not including IDP and refugee women (see, for example, Najafizadeh, 2013; Selimovic et al., 2012; Jocbalis, 2016; Shahnazarian və Ziemer, 2014). This study examines the perspectives of the LGBTQI + / queer communities in Armenia and Azerbaijan and revisits the role of existing peace processes in resolving the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. On this basis, in this article, I illustrate how the existing peace initiatives should change more precisely if they include the participation and understanding of LGBTQI +/queer subjects. This article aims to understand 'why?' and 'how?' the LGBTQI+/queer community is excluded from the peace initiatives and to consider their intersectional experiences and standpoints, I aim to answer, 'how does the peace process have to be re-imagined and re-designed?' What this study adds to existing work is a more explicit focus on the construction of sexuality and intersectional understanding of peace processes that have remained under-examined in the context of the peace processes of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Methodology

The key aim of the research is to explore the effects of the conflict in NK on the lives and concerns of IDP and refugee women and LGBT/queers from Armenia, Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh and to think about how these actors can participate in peacebuilding. A qualitative research design is best suited for addressing these research questions. Qualitative research emphasizes the importance of contextual knowledge, derived from participant-centered methods (Gunaratnam, 2003). As the method of data collection, I chose semi-structured open-ended interviews and participant observation in and around the city of Baku, Azerbaijan and through social media in Armenia. Following these, 10 interviews were conducted in a way that they were attentive to the mutual constructions or creative collaborations (Campbell and Lassiter, 2014).

I contacted participants with the support of colleagues who previously worked in LGBTQI + / queer communities. For LGBTQI +/queer participants, I also asked my queer friends to share their LGBTQI + / queer contacts (in Armenia and Azerbaijan) with me. The study consisted of a total of 5 different interviews and 10 people, conducted through tape recordings and completed with field notes (see, Table 1).

Shortly after this study, a war broke out between Armenia and Azerbaijan in July and September-November 2020, and the Azerbaijani side declared to the world that 'it had won the war, de facto' (Grzybowski et al., 2020). Despite the Azerbaijani side's insistence that the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict is resolved, the Armenian side is not convinced (McLaughlin, 2021). As a researcher, I do not think that this conflict is resolved and in order to resolve this conflict, serious investment has to be made in peacebuilding and every individual must be allowed to participate in this process. Although this study was conducted before the current situation, the results of the study are still relevant for the LGBTQI +/queer community in Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Table I: Compiled Participant Information

Pseudonym | Gender | Age | Ethnicity | Socioeconomic status | Fieldsite | Citizenship |

Lilit | transgender | 30-40 | Armenian | middle-class | online | Armenia |

Eldar | queer | 20-30 | Azerbaijani | working-class | Baku | Azerbaijan |

Hayk | queer | 20-30 | Armenian | working-class | online | Armenia |

Vardan | gay | 20-30 | Armenian | middle-class | online | Armenia |

Leyla | lesbian | 30-40 | Lezgin | middle-class | Baku | Azerbaijan |

Problem statement: Gender inclusion in peacebuilding

According to Cobar (2018), there is no such thing as a gender-neutral peace process. Thus, a gender perspective leads to a gender-sensitive peace and a more inclusive peace which starts with an understanding that policies, processes and peace agreements are gendered. This also means that in peace processes gender is one of the significant categories which unravels the male-centered policies and processes of peacebuilding. As an analytical tool, gender allows us to investigate the power relations in specific situations, and to comprehend the historical development of conflict from a wider perspective.

Processes of exclusion of members of the LGBTQI+/queer community from peacebuilding

Conflict and displacement constitute layers of vulnerability also for LGBTQI+//queer-identified individuals from Armenia, Azerbaijan and Nagorno Karabakh. In this section, I analyse the views of research participants on their exclusion from peace initiatives in relation to the persistent association of queerness with pathology and the fear of queer individuals. In Armenian and Azerbaijani societies, LGBTQI+/queer individuals are often considered an aberration (Dadashzadeh and Paitjan, 2020) since they do not appear to engage in the pronatalist policies. According to Armenian transgender Lilit queers are perceived as being 'incapable of making rational choices', an argument used against their participation in peacebuilding.

'In Armenia, the queer community is not seen as rational individuals and unfortunately, they are considered mentally ill Armenian society thinks LGBT individuals cannot help solving the NK conflict because they first need to solve their own 'mental problem'. Their mental problem being LGBT and not following the traditional values of Armenian society...' Lilit, 46, middle-class, Armenian transgender, YerevanAs Lilit argued queer individuals' mental illness is a product of the heteronormativity and the hatred of LGBTQI+/queer. Here the notion of 'incapable of making rational choices' is associated with the issue of sexuality and thus, queers are seen as mentally sick. This suggests that LGBTQI+/queerness is considered pathology and because of the non-reproductive partnerships and the promoted pronatalist policies, Armenian and Azerbaijani societies consider it as 'illness'. The queer community is excluded because of their assumed 'mental illness' and inferiority [specifically irrationality] that contrasts with the superior 'rationality' accorded to male peacebuilders and their heteronormative identities. LGBTQI+/queers might not be included by women peacebuilders either as Eldar observed:

'There are many privileged women peacebuilders who do not imagine queer individuals in the peacebuilding process. The 'illness' of queer individuals is also perceived (by privileged women) as a barrier for them to participate in the current peace initiative.' Eldar, Azerbaijani queer, Baku.Eldar's observations amplify Lilit's claim of queer abjection in Armenian and Azerbaijani societies. Even this allegedly privileged women peacebuilders might not aim to include the queer individuals in the peace processes because of the manipulation against the queer identities. These suggest that abjection and manipulation obscure the violence, pathologisation and exclusion. Vardan highlighted that women peacebuilders already are, considered marginal figures in the negotiations process because they are minority and Hayk had claimed that many supported the militarisation underwriting the male-dominated peacebuilding process. The perspectives of these minoritised queers in peacebuilding might, therefore, be shaped through male and heteronormative lenses. Together, the pathologisation against queer community is produced through the traditional understanding of heteronormativity in Armenia and Azerbaijan. In this process, hegemonic masculinities are considered decision-makers and thus, they have already labelled queerness as 'mental sickness'. Consequently, the male-dominated peace process kept the queer community out of the peace processes. Therefore, on the first level, LGBTQI+/queer community is considered a 'non-contributory' subject for the resolution of the Nagorno Karabakh conflict.

The second level of analysis focuses on the fear of queers within the peace processes. Leyla told me that some peacebuilders think that LGBT/queer empowerment can cause a serious problem of loss of trust) in the peacebuilding process for many citizens in Armenia and Azerbaijan. The research participants argued that the inclusion of queers in peace processes is supported only by pro-western peace activists and organisations. Consider Hayk's account:

'Queer people's involvement is seen as problematic and queers are excluded [in peace initiatives] because of the irrational fear against them… Many men and privileged women peacebuilders think if queers are involved in this process, people will hate peacebuilding even more…. But I believe that people will get used to the visibility of queers in each part of life, especially in the peace process if these 'peacebuilders' stop the manipulation against us.' Hayk, Armenian queer, NetherlandsHayk considered that Armenian and Azerbaijani peacebuilders actively manipulated citizens' thoughts so as to not include the queer community in the peace processes. The peacemakers, Hayk is referring to, are mainly representatives of non-governmental peace organizations (NGOs) who have been working in this field for many years. However, there are many peace activists among the younger generation who continue the homophobic path of those peace NGOs. This means the involvement of the queer community in peace processes does not benefit homophobic cisgender NGO leaders and others. This suggests that there is a strong anti-queer propaganda within the peace processes, which both feeds of and reinforces the hatred and homophobia on the societal level. Homophobic mindsets (Carroll and Quinn, 2009) are fuelled by the idea of 'mental illness' of queers.

It also shows that the 'fear' against queers in the hate speech of government officials is socially established. Because of this propaganda, people perceive queerness as a problematic category, and the inclusion of the LGBTQI + / queer community in peacebuilding activities and initiatives becomes a problem in Armenian and Azerbaijani societies. At the same time, as Hayk said, people's growing hate towards peace process remains one of the unanswered questions of the peace process. In other words, it is questionable how the homophobic Azerbaijani and Armenian societies will react to the involvement of the queer community in these processes. For example, in the Second Karabakh War in 2020, non-queer young peace activists were stigmatized as the 'enemy of the nation' in both Azerbaijan and Armenia.

In the event that peace activists, from the militaristic Azerbaijani and Armenian societies, join the peace processes, such reactions will inevitably result in a stronger anti-peace and homophobic response. To put it differently, queers and peace activists will face intersectional hate speech, which is a constant process in militaristic systems. Therefore, Hayk thinks that the queer community is not purposefully involved in the peace process, and it cannot last forever. However, these are still the rules set by the heteronormative system, and the queer community must be able to overcome such difficulties, either through protests or peacefully.

Processes of inclusion of members of the LGBTQI+/queer community in peacebuilding

As a result of this qualitative research, I propose the following three suggestions that can contribute to re-designing the peace process and include LGBTQİ+/queer community in these peace processes in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict:

Firstly, to widely publicise and prepare open and secure environments for LGBTQI+/queers to articulate and share experiences that can then inform other people about the presence of these peacebuilders within the process. This will allow them to become a part of the peace processes because many research participants did not have information about the current peace initiatives. Therefore, queers need to set up their own peace fora to increase their leadership and get access to the peace processes in the context of the NK conflict.

Secondly, consciousness-raising among queers can enhance their active participation in the current peace processes. The main aim of consciousness-raising is to show to many queers that as long as they do not raise their voices, nobody will solve the NK conflict. People who are responsible for such consciousness-raising should be LGBTQI+/queer citizens of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh who can start the grassroots movement of these communities. In the small groups, LGBTQI+/queer individuals can organise the events and gatherings in order to share their own experiences and stories which can help them to understand the role of consciousness-raising in peacebuilding. Thus, the consciousness-raising process must be organised as a grassroots movement by local communities, activists and peacebuilders.

Lastly, introducing a quota system is an important step towards including more queers and minoritised ethnic people in the peace processes. The basic premise of the quota system in peacebuilding activities is to provide queers' representation at all levels and aspects of the current peace initiatives (usually within a set period of time). Active participation through the legislation provides more coherent and less challenging empowerment. The introduction of such strict measurement should become a part of the national conventions in Armenia and Azerbaijan and this can help to change the misperceptions of the society about the queer community. However, quotas are not long-term action plans and they must always be adapted to the specific cultural and socioeconomic situations.

Conclusion

To sum, exclusion of queer community emerges on two mutually reinforcing levels: mental illness and fear of queers that undergird their exclusion from the peace processes. The accounts of LGBTQI+/queer research participants suggest that they contribute critical societal analysis and an alternative vision of peace to the peace processes in ways that challenge the heteronormativity of Armenian and Azerbaijani societies. In particular, LGBTQI+/queer identified people tend to emphasise an anti-militarist perspective and endorse a diminishing of the role of the military in the NK conflict. The involvement of queers in the peace process will not only contribute to resolving the conflict but also increase the visibility of queer community. The visibility of queers may help dismantle ideas of mental illness, pathology and' fear' against queer community. Therefore, the inclusion and representation of queers in the peace process play a vital role for the queer community of Armenia and Azerbaijan.

References

Abubakirova, Sabina. 2020. 'Rumours of Violent New Anti-Queer Group Spark Worry in Azerbaijan'. 2021. OC Media (blog). https://oc-media.org/rumours-of-violent-new-anti-queer-group-spark-worry- in-azerbaijan/.

Akhundov, Jafar. 2017. 'Rise of Militaristic Sentiment and Patriotic Discourses in Azerbaijan: An Analytic Review'. Caucasus Edition–Journal of Conflict Transformation, 1–17.

Campbell, Elizabeth, and Lassiter, Luke Eric. "Doing Ethnography Today: Theories, Methods, Exercises." Wiley-Blackwell 4, (2014): 1-160.

Cobar, Jose Alvarado, Emma Bjerten-Gunther, and Yeonju Jung. "Assessing gender perspectives in peace processes with application to the cases of Colombia and Mindanao." SIPRI Insights on Peace and Security 6, (2018): 1–32.

Daigle, Megan, and Myrttinen, Henri. "Bringing Diverse Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (SOGI) into Peacebuilding Policy and Practice." Gender & Development 26, no. 1 ( 2018): 103–20.

Gunaratnam, Yasmin. Researching Race and Ethnicity Methods, Knowledge and Power. London: SAGE, 2003.

Grzybowski, Janis, Giulia Prelz Oltramonti, and Agatha Verdebout. "Fault Lines of a War Foretold." Eurozine, 2020. Available at: https://www.eurozine.com/fault-lines-of-a-war-foretold/. Last accessed: May 15, 2021

McLaughlin, Daniel. "Armenia says conflict with Azerbaijan' unresolved' as Kremlin hosts talks." The Irish Times, January 11, 2021. Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/armenia-says-conflict-with-azerbaijan-unresolved-as-kremlin-hosts-talks-1.4455744. Last accessed: May 15, 2021

Mindaugas, Jocbalis. "Transformative Gender Narratives in South Caucasus: Conversations with NGO Women in the Armenian-Azeri Conflict." Malmö högskola/Kultur och samhälle, 2016. Available at: http://muep.mau.se/handle/2043/21318. Last accessed: May 15, 2021

Najafizadeh, Mehrangiz. "Ethnic Conflict and Forced Displacement: Narratives of Azeri IDP and Refugee Women From the Nagorno-Karabakh War." Journal of International Women's Studies 14, no. 1 (2013): 161–183.

Paitjan, Ani, and Dadashzadeh, Naila. "Armenia and Azerbaijan: Cross Views on Army and Homosexuality." Caucasus Edition–Journal of Conflict Transformation, 2020. Available at: https://caucasusedition.net/armenia-and-azerbaijan-cross-views-on-army-andhomosexuality/. Last accessed: May 15, 2021

Selimovic, Mannergren Johanna, Nyquist, Brandt Asa, and Soderberg, Jacobson, Agneta. "Equal power - lasting peace: obstacles for women's participation in peace processes." Kvinna till kvinna, Johanneshov, 2012. Available at: http://www.equalpowerlastingpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/EqualPower_print.pdf. Last accessed: May 15, 2021

Shahnazarian, Nona, and Ziemer, Ulrike. "Emotions, Loss and Change: Armenian Women and Post-Socialist Transformations in Nagorny Karabakh." Caucasus Survey 2, no. 1-(2014): 27–40.

Walsh, Sinead. "Nagorno-Karabakh: A Gender Inclusive Approach to Peace." openDemocracy, 2014. Available at: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/nagornokarabakh-gender-inclusiveapproach-to-peace/. Last accessed: May 15, 2021

Zamanov, Ramil. "Gender, ethnicity and peacebuilding in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict." Charles University, Faculty of Humanities, 2020. Available at: https://dspace.cuni.cz/handle/20.500.11956/123476. Last accessed: May 15, 2021

Comments